Identity is composed of notions of who we are, who others say we are (in both positive and negative ways), and whom we desire to be . . . Our identities (both cultural identities and others) are continually being (re)defined and revised while we reconsider who we are within our sociocultural and sociopolitical environment. Idenity is fluid, multilayered, and relational, and is also shaped by the social and cultural environment as well as by literacy practices . . .

-Gholdy Muhammad, Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy (Scholastic, 2020), 67.

Who do our students see reflected back at them in the classroom? If identity is the dynamic dance between who we think we are, who others assert we are, and who we want to be, what music are we as educators using to facilitate this dance for our students in the learning environment? What does our lyrical content, rhythm, tempo, and melody tell the learning community about itself–or at least, confesses what we believe about it? Do we create harmony and space to build beautiful life-affirming crescendos, or do we play a cacophonous discord of developmental harm?

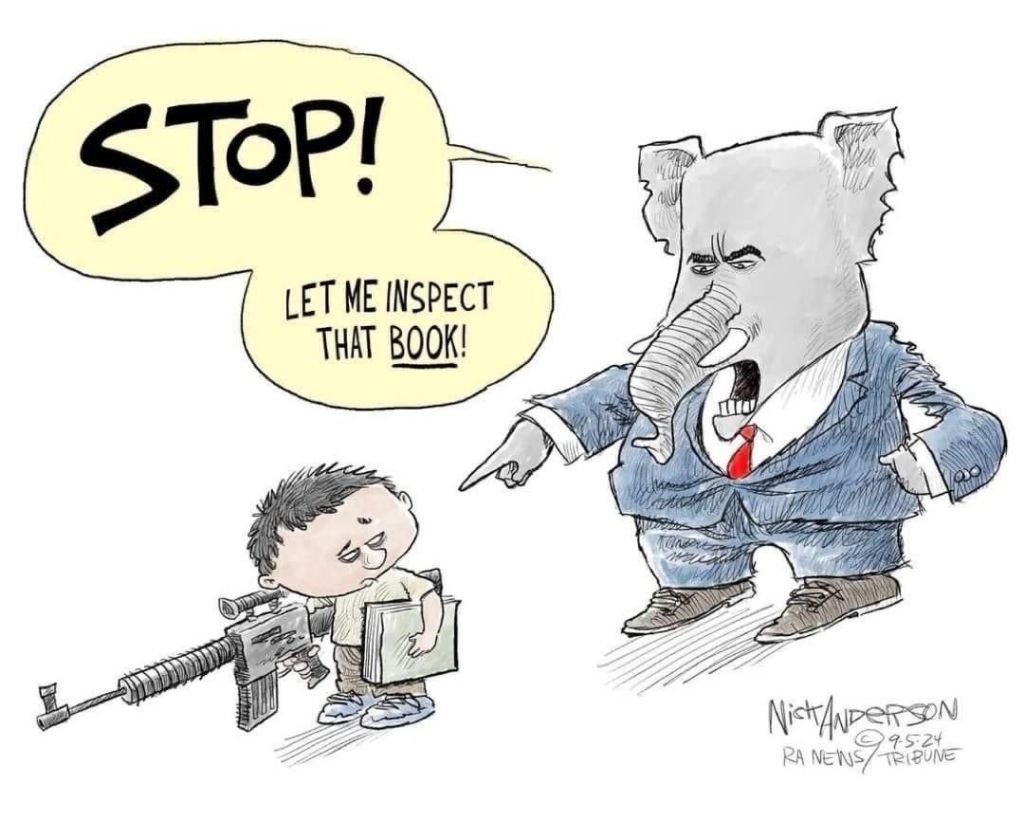

Arguably, identity is at the heart of the matter in the ongoing battles over curriculum and information access (i.e. book banning) in public schools across the nation. Curriculum that provide opportunities for students to “deeply know themselves and the histories and truths of other diverse people . . . ” and to learn “about the cultures of [others] . . . ” so that they might know “how to respect, love, and live in harmony with others who don’t look or know the world as they do”1 is under fire by those who have enjoyed a privileged identity reflected the archaic imagery of what once was considered the national identity.2

Some laws and political stances, such as those in Idaho, Tennessee, Florida, and other states, both reinforce the archaic national identity and its privileging as well as argue for a position that students are to wait until “college or adulthood to discover self for the first time.”3 These same practices suggest that student identity is defined solely by students’ parents or guardians until they become adults. These practices harm students and produce emotionally and intellectually stunted adults. While being emotionally and intellectually stunted and lacking a sense of identity is ‘fine’ for those insisting on such laws and practices, it is unhealthy and harmful to our students.

Within every classroom, a set of educational standards and objectives are laid out. The goal is literacy. By literacy, I mean more than reading and writing. I mean literacy as “connected to acts of self-empowerment, self-determination, and self-liberation” and the accumulation of knowledge and the use of skills “as tools to further shape, define, and navigate their lives.”4 However, “[before] getting to literacy skill development such as decoding, fluency, comprehension, writing, or any other content-learning standards, students must authentically see themselves in the learning.”5 It is vital that students see themselves as equal partners in an educational experience that aims to help them develop into educated and fully realized humans, rather than passive spectators gaining skills from the leftover scraps of those who have been privileged to be active participants.

This requires that I, as an educator, must first see my students. I must discover who they are and the assets they bring to the classroom through their diverse backgrounds, languages, and experiences. Every student carries with them “funds of knowledge”6 that can be leveraged to their advantage. It is up to me, and all educators, to tap into these funds to better reach and teach our students. Moreso, we can use these funds to reflect our students back at themselves in the classroom in ways that both increase their literacy skills and allow them to further develop their identity.

The music I wish to orchestrate in my classroom is one that will facilitate a healthy dance between the intersecting elements of identity. As my students learn to critically evaluate Texts,7 apply logic and reason, question, challenge, and build up the tools with which they will transform the world, I want them to see themselves and others through a lens of humanity. Some might argue that recognizing culture, language, gender-identity, ethnicity, and race are counter-intuitive to a human centered lens, but these fail to understand the multifaceted elements and experiences that make us human. Likewise, these elements inform us of the conditions and experiences of others–allowing us to take note and intervene when the life and well-being of our fellow humans are placed at risk. To be honest, I believe that it is the fear of our students’ understanding of humanity that motivates those who argue against our students’ access to education and information.

Education is liberation, and liberation threatens the status quo; it disrupts the power structure. If our students learn to authentically see and understand themselves, defended by a bulwark of education and literacy, then they will be much harder to control. They will be less likely to accept the identities thrust upon them by others. When students see themselves in the curriculum, when they discover how literacy can give shape to their identities and understanding of the world around them, I theorize they are more likely to buy into the work it will take to ultimately empower them to create their own paths and forge their own destinies.

———-

1. Gholdy Muhammad, Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy (Scholastic, 2020), 67.

2. The national identity is composed of the myths, legends, and edited stories of the United States that portray white Western, Judeo-Christian ideals and white men as the Paragons of America. Non-white and non-cis-heteronormative people are considered “lesser” or “less than” American when compared to white, cis, heteronormative, American men. This is reflected in cultural dog whistles, state and federal laws, policies and practices, and our societal institutions. Several texts are available which explore this issue in great detail, including: White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity by Dr. Robert P. Jones, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together by Dr. Heather McGhee, Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, and Pedagogy by Dr. April Baker-Bell, Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement by Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, et. al., and many others. (Yes. I have read all of these texts, and I strongly recommend them them.)

3. Muhammad, Cultivating Genius, 67.

4. Muhammad, Cultivating Genius, 22.

5. Muhammad, Cultivating Genius, 69.

6. Norma Gonzales, Luis C. Moll, and Cathy Amanti, Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Household, Communities, and Classrooms (Routledge, 2005).

7. By “Texts,” I mean capital “T” Texts. Texts refers to more that just the written word. It referst to all media, information sources, systems, policies, practices, life scripts, and every medium by which we come to know ourselves and the world around us.